Here’s an interesting variation on the the shadow box fence (where the infill boards are placed on alternate sides of the rails) taken in Kamakura outside Tokyo. Using 5 rails here instead of the more typical two or three imparts the impression of a basket weave. Metal flashing protects the top from water although the wood has been left to weather naturally.

Post and Beam Fence

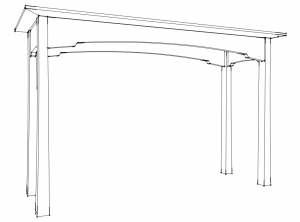

Timber Frame Gate

Short Bamboo Fence

Frame and Panel Gate

Timber Frame Gable

Fence–Design

I thought about fences for what seemed like years, looked all over for inspiration, contemplated material lists in Manila, shot promising examples in Japan. We were replacing a 40 inch cyclone fence and wanted something more appealing than the typical lattice over board infill designs popular in the area (imagine pressure treated 4×4 posts, pressure treated 2×4 rails, 1×6 cedar infill to 5 feet and a foot of 2 inch lattice above), although anything would have been an improvement over the chain link.

Requirements:

- Suitable for the house

- Wood

- Scaled for a small yard

- 6 feet high with a ~5 foot privacy panel and ~1 foot lattice top

This design featured in a California Redwood Association brochure provided the starting point for our design. Source.

It was surprisingly difficult to find something we liked (see here and here for useful resources). In the end, we modified a design featured in a California Redwood Association brochure. The six-foot high fence consists of alternating panels of of four- and eight-foot length supported by four-by-four posts. Alternating wide and narrow boards (wide-narrow-narrow-wide) compose the privacy section of each panel, but the tops of the short and long panels differ. The short panels feature a simple vertical and a gable tops the long panels. We liked the alternating gable tops and the use of wide and narrow boards but used panels of the same length, spacing posts 6 feet on center to suit the size of the yard.

A narrow table–construction

I don’t like dimensioning rough stock, but my local sawyer had a good price on red alder. So construction began with a lot of time on the jointer and planer. Once I’d prepped my stock, I chose the best boards for the tops and glued them up.

While the tops dried, I prepared the template for the long aprons, then cut the blanks. The pattern was roughed on the bandsaw, then each apron was routed to final shape using the template to guide the router. While the original design called for a stepped arch on the short aprons as well as the long, they made the table look too busy, so I went with straight aprons for the sides.

After cutting the tops to final size, I added a two-inch bevel along the bottom edges. The long bevels were cut on the table saw. Since the top was far to long to bevel the short edges on the table saw. I used scrub and smoothing planes to bevel the shorts ends.

The legs began as 8/4 stock roughed out to 1.5″ blanks. Before cutting the tapers, I pre-drilled for hanger bolts. Another template simplified reproducing the curved taper 16 times with the router.

After sanding all parts through 220 grit, I wiped on three coats of blond shellac, then lightly wetsanded with 400 grit to smooth things out once the shellac had cured.

Then it was time for assembly. I attached the aprons to the to the top through pocket screw holes after reaming out the holes to allow the top to expand freely. To allow the tables to knock down for transportation, the legs were attached using hanger bolts and corner blocks.

A narrow table–design

I eyed the metal and “wood” desk with some trepidation from my vantage point on the inflatable mattress. My sister’s guest room was small enough that you couldn’t sit in the chair at the desk with the bed inflated. Had the outward curving metal legs run straight down instead, it might have worked. Clearly a piece designed for the space would make things more usable. Since her birthday was coming up, I offered to build her something. I took some measurements, and sent her some photos to consider.

I eyed the metal and “wood” desk with some trepidation from my vantage point on the inflatable mattress. My sister’s guest room was small enough that you couldn’t sit in the chair at the desk with the bed inflated. Had the outward curving metal legs run straight down instead, it might have worked. Clearly a piece designed for the space would make things more usable. Since her birthday was coming up, I offered to build her something. I took some measurements, and sent her some photos to consider.

The space was about eight feet wide and 18 inches deep, which suggested a parson’s table, but I needed to be able to transport the finished piece. In the end I decided two tables would be more practical and more flexible. After some consideration and taking an online furniture quiz, my sister reported she liked “Asian style” furniture. So the design brief called for two tables 30″ high x 48″ wide x 18″ deep and “Asian” in style. An overhanging top and reverse taper legs could evoke a torii gate. I also like the stepped arch Darrell Peart uses in some of his work and wanted to incorporate it. The arch adds a little visual variety and echoes the curves of the legs.

Limbert No. 81 Hall Chair–Construction

The original design was executed in quartersawn white oak. Because I wasn’t sure I wanted to keep the chair, I chose common pine to create a prototype. Building the prototype afforded the opportunity to verify my drawings and practice construction, then live with the chair for a while before deciding whether I liked it enough to build a final copy in another wood.

Construction began with gluing up the blanks that would form the seat, sides, and back. The notch at back of the seat is beveled to match the slope of the chair back and to fit the back’s sloping sides. I could have cut things square using a jigsaw or bandsaw, then beveled the notch with chisel and block plane. Instead, I assembled the blank from three pieces, two narrow ones surrounding a middle piece sized to the width of the back where it met the seat. I cut a bevel on that middle piece before assembly, then glued up the blank. While the blanks dried, I cut the apron and stretcher to size.

With the blanks out of the clamps, I laid out the shape of the back and cut close to my layout lines on the bandsaw, then planed things to final size with my No. 7 jointer. To produce the cutout, I drilled out the radiused corners and sawed out the waste with a jigsaw. That approach left a lot of cleanup with rasp and block plane. In retrospect, it would have been a lot easier to throw together a quick template to guide a router.

And that’s the approach I took for the cutouts on the sides after cutting the blanks to final size. The ends need to be beveled to 5 degrees to create the appropriate slope, which I cut on with the table saw set to the appropriate angle. The notch on the base was cut on the bandsaw. After roughing out the cutouts, I attached my template (four pieces of scrap held together with pocket screws), and routed the final shape of the cutouts.

Since I was using a pretty nondescript board, I decided on a finish of black milk paint. I sanded to 180 grit then used a foam roller to apply three coats, lightly sanding with 220 between the first and second coats to remove raised grain. Once the paint was dry, I was ready for assembly.

Like much of Limbert’s slab-sided furniture, the No. 81 was probably dowelled together. Dowels offered an economical way to join angled pieces together in a production environment. For the prototype, I used pocket hole screws. It’s a less-than-ideal joint for something like a chair that can see a lot of abuse, but they let me get the prototype together quickly. I drilled my holes, clamped the sides to the aprons using angled clamping blocks, and screwed the base together. Then I attached the seat followed by the back. On the original chair, the back was screwed to the edge of the seat and to the bottom stretcher and the screw holes plugged with oak buttons. I screwed the back on and plugged the holes, then cut the plugs flush. After some touch up paint around the plugs, I wiped on a couple of coats of boiled linseed oil and some dark paste wax.

The finished chair seems smaller in person, slightly unassuming for such an iconic design. And it’s not especially comfortable (I sometimes cynically wonder if that is intentional, a design meant to hurry guests in or out of the entry way). Rendered in black and divorced from the quartersawn white oak that characterized most Arts & Crafts furniture, it also seems curiously timeless. The lack of color highlights the accomplished use of positive and negative space and the dynamic intersection of angles. In fumed oak, it’s at place in the Arts & Crafts home, but done in maple or teak and it could pass for Danish modern. In black or white, it could pass in an industrial loft. I still haven’t decided if I’ll do a final copy, and if I do, it will be hard to choose what wood and finish to use to give it its character.