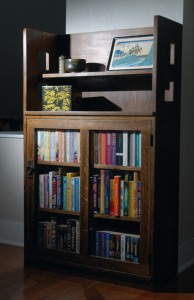

My son has been enjoying The Police lately, so I’ve had ample time to contemplate the old TV stand I replaced last year, which now serves a stereo stand. I’m reminded of the difference time, taste, skill, and resources can make in a design. I’ve built three TV stands over the last fifteen years, and each one encapsulates the capabilities and materials available during construction.

The first was plywood, the shelves cut to size by the local lumberyard and housed in dadoes cut in the 2 x 4 legs with a circular saw. Screws secured the shelves to the dadoes. Then I finished it using paint leftover from an apartment remodel. The circular saw and cordless drill used to build the stand represented the bulk of tool collection at the time. The slanted front echoed the ladder bookshelves I’d built for the living room, and each shelf was designed for a specific component–receiver, VCR, and DVD player. Continue reading