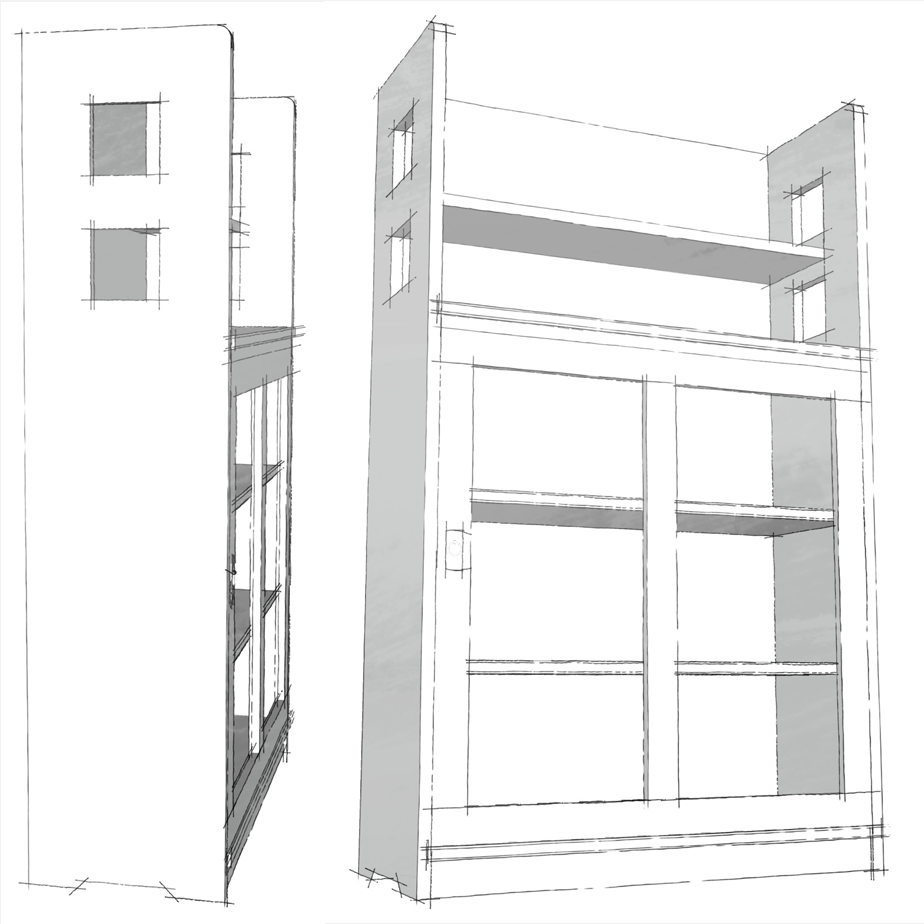

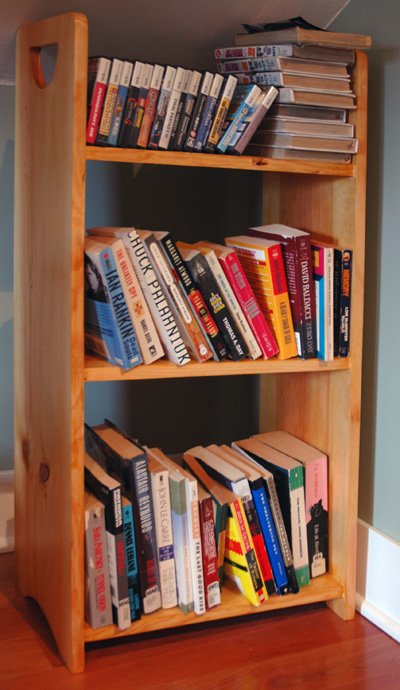

A slightly modified Stickley Number 79.

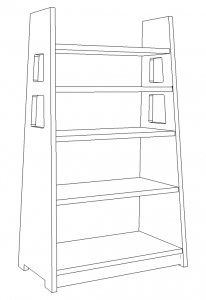

When the time came to replace the utilitarian shelves in my office, I knew I wanted something in the Arts & Crafts style, but the sloping ceiling and short knee walls create some design constraints, and I needed a design that lent itself to production techniques. After checking my library for options, I decided one variation or another of the magazine stand would match my design and construction requirements.

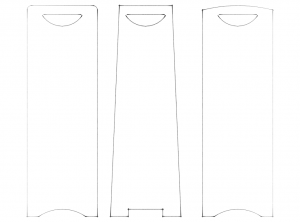

Initially drawn to the trapezoidal forms produced by the Charles Limbert Company, I prototyped a couple. While they add some visual interest, the tapering sides required cutting three different shelves for each stand, complicating construction. After some experimentation, I settled on a modified version of Stickley’s No. 79. This iteration of the form features rectangular sides softened by radiused corners on the top edge, a half-moon cutout to form the handle, and an arch on the bottom edge. A router template would make reproducing the sides relatively easy, and the straight edges of the sides meant that I could cut the shelves without having to change any tool setups.

Detail of the modified Stickley design.

I modified the design to better fit the space and my requirements. I reduced the height from 40

inches to 36, lowered the bottom shelf to increase storage capacity, and increased the radius on the top corners. I also added a couple of inches to the width of the shelves and eliminated the toekick. With the design finalized, I prepared a full-sized router template in 3/4″ plywood.

Since I had a lot of shelves to build, I chose #3 pine. It’s readily available in wide boards and economical. The blanks were cut to slightly oversized on the tablesaw, then attached to the template. Had I been placing all the shelves in the same position for each stand, I could have screwed the template into each side so that the shelves would have hidden those screw holes. But I needed to be able to adjust the height of the shelves, so I used double-sided tape to attach the template to the blanks, then roughed out the shape of sides using the jigsaw and trimmed to final dimensions with a flush-cutting bit in the router.

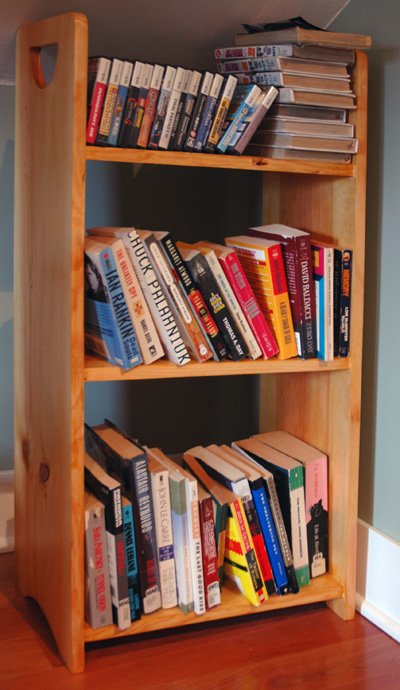

When I can, I like to pre-finish my projects before assembly. It can increase the time spent on finishing, but it simplifies the process. After sanding through 220 grit, I wiped on three or four coats of amber shellac. Once the shellac was dry, I wet sanded with 400 grit. Joinery is simple: two pocket hole screws in the end of each shelf join the stand together.

A knee wall of magazine stands.